Building Resilience

Originally posted on 31st August 2022.

“Do not judge me by my success, judge me by how many times I fell down and got back up again” - Nelson Mandela

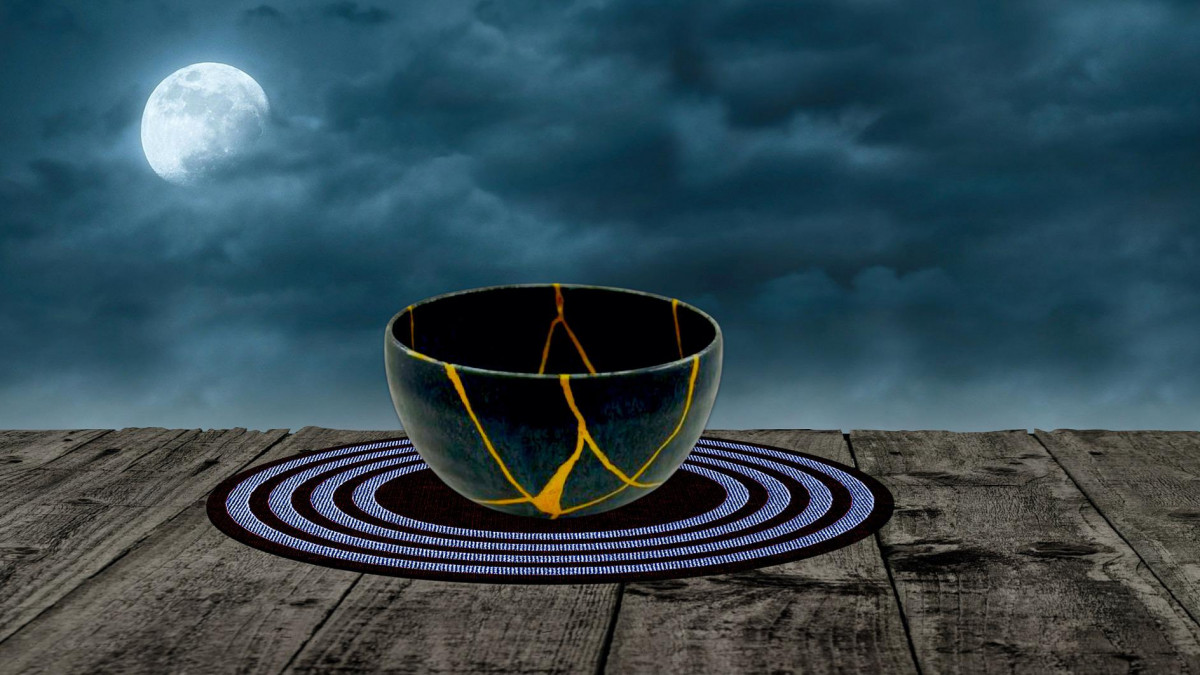

The Japanese art of Kintsugi is a way of repairing broken pottery using lacquer and powdered gold, and to me, it is such an elegant way of demonstrating resilience. Not only does the pottery become whole again, it takes on a new life with beautiful golden seams. In the same way, when we face challenges, we may fall and shatter, but we have the opportunity to not just pick ourselves up, but to put ourselves back together and become a better version of ourselves because of it.

To do this, we need to be able to show resilience.

But what does this actually mean? The Cambridge Dictionary defines resilience as ‘the ability to be happy, successful, etc. again after something difficult or bad has happened.’ Children who are resilient have been shown to be braver, more curious, more adaptable, and more able to extend their reach into the world. Some people talk about resilience as ‘bounce-back-ability.’ Whatever you choose to call it, the good news is that it is a skill, and like any other skill, it can be built over time. Of course like any skill, if we want to master it, the younger we start the better.

Let’s talk science for a second.

This is your brain

It hasn’t changed much since we were cavemen, so the response isn’t really all that useful, and that’s why we often struggle when we’re stressed. Read on to find out more.

Our bodies respond to stress with a number of physical changes. For children, they often feel stressed before a sports match, or a music recital or test. Think back to a time when you were stressed, maybe about work, money, relationships. How did your body feel? Maybe your heart was beating faster, or you felt hot and sweaty? This is because the amygdala, the part of the brain responsible for our instinctive, impulsive responses, reacts immediately to anything which it thinks may be a threat. It sends messages to the brain to release its chemicals, including adrenaline and cortisol, to help the body deal with the stress. While the stress is ongoing, the physiological changes stay switched on. The purpose of this when we were cavemen was to help us to be faster, stronger, and more able to deal with short-term threats like saber-tooth tigers attacking us!

However, nowadays our stresses aren’t usually from a physical threat, they’re usually from worries about school, friendships, jobs. These stresses tend to be longer-term, and the problem with this is that if we are always stressed, then the way our body responds can weaken our immune system, which can make us more likely to fall ill. This is why we often get sick at the most inconvenient times like just before a really important exam or interview!

The other thing stress does is shut down the prefrontal cortex. This is the part of your brain that is involved in paying attention, problem solving, impulse control, and regulating emotion - our ‘executive functions.’ In other words the pre-frontal cortex is our emotional control centre. It tells the panicking amygdala to stand down for a second and think before acting, which is often a much more effective way of dealing with the types of stresses we tend to face nowadays. Resilience is the ability to keep the pre-frontal cortex switched on, and calm the amygdala down.

Let’s return to resilience.

Children who are less resilient tend not to be able to cope with stress as well as children who display high levels of resilience. Whether you’re a parent, teacher, child or teenager, it’s likely that as you’re reading this, two people will come to mind - one who seems to take everything in their stride and one who gets flustered at what appears to be the tiniest problem. When demands that are being put upon young people outweigh their capacity to cope, it can manifest in different ways; they might become emotional, they might withdraw, or they might become defiant, angry or resentful. We all have moments where we display these kinds of behaviours, but for people with low resilience, it becomes a pattern of behaviour, and if it’s not addressed when we are young it becomes increasingly difficult to do so when we are fully-grown adults.

How to help children increase resilience:

1. Build their executive functioning - paying attention, problem solving, impulse control, and regulating emotion:

- Paying Attention: Play memory games with them, limit screen time, set timers, give short and clear directions, teach them to meditate (particularly meditations which involve listening until a sound disappears.)

- Problem Solving: Play puzzle games with them, ask children ‘why’ or ‘what would happen if’ questions, allow them to get creative, let them make decisions for themselves, model effective problem-solving by talking out loud when you’re working out how to resolve your own challenge.

- Impluse Control: Play turn-taking games with them, teach them to take a step back (counting to 3 helps), allow them space to learn through natural consequences, explain the ‘why’ of any rules - children often respond better if they understand why.

- Regulating Emotion: Help your child to recognise and name what they are feeling, model self-regulation so they know what it looks like, teach them how to take deep breaths, make sure they are getting enough rest and are physically healthy, and above all do not remove them from the possibility of encountering difficult situations where they could become dysregulated - after all, practice makes perfect and the more opportunities you give them to practice self-regulating, the better they will become at it.

2. Build a supportive and nurturing relationship with them. Let them know it’s OK to ask for help - as much as I preach teaching children to be independent, this doesn’t mean that you are never there to step in when it just gets too tough for them to handle on their own. They’re human, and they’re learning. We all need help every now and again, and they need to feel it’s safe to ask for it. Research tells us that it’s not rugged self-reliance, determination or inner strength that leads kids through adversity, but the reliable presence of at least one supportive relationship, and this can be anybody who is involved in the child’s life - a parent, teacher, coach, other family member - the more social support they have, the better.

3. Teach them how to reframe. By this I mean taking an unpleasant or unwanted situation and looking at it a different way. It’s so important here to understand that the purpose isn’t to ignore that your child is disappointed or upset - use this as a chance to build their emotional regulation skills - but then take the focus away from the disappointment and help your child to look to the opportunity they now have. For example, if your child wanted to go to a theme park, but the rain means they can’t do it, then acknowledge the disappointment they are feeling, before gently asking them what they can do now their day is free?

4. Give them powerful language. Using self-talk is a great tool for helping us to problem-solve. Instead of offering up solutions to a question your child has, ask them what they think would work. Questions like:

- How could you break the problem down?

- What has worked before?

- What do YOU think could help you?

5. Show them you trust them to be OK. How many of you reading this have seen a child fall over and immediately look to their parents for an idea of how to react? If their parent is worried or concerned, they are more likely to cry, but if the parent continues on as normal or doesn’t make too much of it, the child is usually happy to pick themselves back up and carry on. Children will take their cues from us as their trusted adults on how to respond to any bump, fall or failure in their lives, and if we show them that we know they will be OK, they are more likely to believe it themselves and develop greater resilience when life does throw challenges their way.

6. Let your child take risks. By allowing them to take controlled, low-stake risks, your child will begin to learn their boundaries. Even better, they learn their boundaries through their own experience which is infinitely more powerful than if we tell them where those boundaries should be. If we do that, we limit them by placing boundaries through our own lens; our own fears and perceived failures in life.

Taking Risks

A friend of mine is so fantastic at allowing her son room to explore and take risks - we met up recently with another friend to go for a walk in a country park and have a catch up. There happened to be a well-known high ropes course at this park, and both myself and our other friend were unsure whether she should allow him to go on it alone - after all it was very high and he’s only 6! She insisted he would be fine and so we watched with trepidation as he eagerly took off, and guess what? He was fine! Better than fine, he had an absolutely fantastic time, and went round the course three times! If our friend had chosen to hold him back because of our fear being projected onto him, he would have missed out on this great experience, one which teaches him an invaluable lesson: that he is capable.

Resilience then, is about allowing a child to take carefully considered risks, knowing that they have a solid support network to fall back on. It is allowing them to be independent and encouraging them to think for themselves, while providing them with the tools to do this effectively. To teach a child to be resilient is the greatest gift you can give them because they know they are not only loved unconditionally, but trusted implicitly.

Categories: : Life Skills, Resilience

Rosey

Rosey